Boltzmann Tulpas

A Work of Anthropic Theory-Fiction

(Why do you find yourself to be a human, living right before a technological singularity? Why not a raccoon, or a medieval peasant, or some far-future digital mind?)

The Dreams of Greater Minds

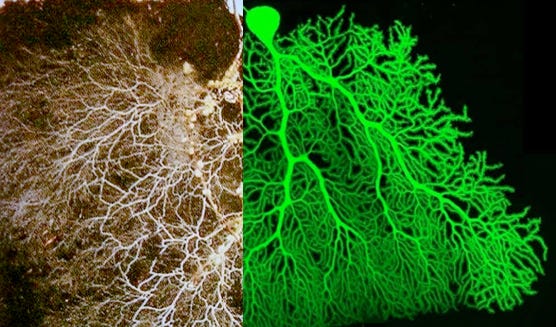

Somewhere, in some universe, there’s an Earth-like planet that has, independently, evolved life. The dominant form of this life is a fungus-like organism that has, essentially, won at evolution, growing to cover the entire planet to the exclusion of other life forms. Having eliminated its competition and suppressed internal mutations, this organism only needs to stay alive—and, for the past few billion years, it has, capturing the vast majority of sunlight incident on the planet’s surface in order to not only sustain itself, but power the activities of the massive underground mycorrhizal network whose emergent information-processing capabilities allowed it to dominate its environment. The long, intricately branched cells of this network saturate the ground, weaving among one another to form dense connections through which they influence the behavior of one another much like neurons.

Over the course of its evolution, this network evolved a hierarchy of cells to organize and coordinate its behavior—a multi-layered system, where lower-level cells sensed the environment, modulated behavior, and passed information up to higher-level cells, which integrated this information to form abstract representations of the environment, computing dynamics via these abstractions in order to pass behavioral predictions down to lower-level cells.

Once the planet had been saturated by its roots, to the exclusion of other life, this network effectively became the biosphere, leaving nothing left to model but its own behavior. To this end its hyphae are constantly forming models of one another, models of themselves, models of these models—and, through these complex, self-referential models, they are constantly imagining, thinking, and dreaming. The surface of the entire planet is as a vast, loosely-connected mind, with the trillions of cells running through every cubic meter of mycelium doing as much collective computation as the hundred billion (massively overengineered) neurons in a human brain. This greater mind dreams of possible systems, in the most general sense.

Dreamt Constructs

If you were to do a Fourier transform of the network’s global activity, you’d find that the lowest frequency modes act as conceptual schemas, coordinating the functional interpretation of various kinds of intercellular activity patterns as though these patterns represented ‘kinds’, or ‘things’ that have kinds, or ‘relations’ between sets of things or kinds; they structure the metaphysics of dream content. Higher frequency modes implement this metaphysics, by determining the extent to which the properties of things arise through their relations with other things or through properties associated with their kinds.

If you were to analyze activity spatially, you’d find that localized regions dream of specific things, in specific relations with specific properties. Physically lower levels of the network add successively finer details to the specifics of higher levels.

Constraints on the kinds of things that are dreamt of, given through metaphysical trends and conceptual schemas, propagate downward, eventually specifying every detail of the dream, until the result is a coherent, self-consistent world. The end result is that all sorts of computational systems are dreamt up by countless localized instances of mind that then attempt to understand them. Almost all such worlds are very strange, simple, or alien: many of them are about endlessly sprawling cellular automata, others run through hundreds of millions of instances of fantasy chess-like games. Usually, the moment that no more interesting phenomena emerge, a dream world dies out; like physicists, local minds attempt to comprehend the dynamics of a computation, and then move on to the next computation once they’ve done so.

As a consequence, the worlds aren’t simply played out step by step according to their own laws of causality; their dynamics are compressed as they’re understood. For instance,

An unimpeded glider in a cellular automaton would not be simulated for trillions of steps; its path would simply be comprehended in an instant; its ‘closed-form solution’ is clear, and can be extrapolated.

The chaotic motion of a double pendulum would only play out for as long as it takes the local patch of mind dreaming of it to comprehend the manner in which the motion cannot be directly comprehended—and in this process, the mind’s manner of dreaming of its motions would send it jumping back and forth through time and its state space, looking for the idea of that kind of motion, the pattern of that kind of motion, the way that that kind of motion is possible.

Totally unpredictable chaos isn’t interesting, and neither is totally predictable order; it’s between the two that a computational system may have genuinely interesting dynamics.

Of course some of these systems end up looking like physical worlds. These are almost never very interesting, though. That general covariance, for instance, should be a property of the substrate within which dreamt objects differentiate themselves from one another, follows almost universally from very simple metaphysical assumptions. Dreams of worlds shaped like vacuum solutions to the Einstein equations—which are almost a direct consequence of general covariance—are, as a consequence, relatively common within those parts of the greater mind where metaphysical laws lend themselves to the construction of systems that look like physical worlds; the moment these worlds are fully comprehended as possible systems, they’re discarded.

Sometimes, though, the structures in a dreamt-of world give rise to emergent phenomena: complex patterns at larger descriptive levels than those at which the dream’s laws are specified, patterns that cannot be directly predicted from the laws. Then a local mind’s interest is really captured. It zooms in, elaborating on details in those regions, or re-runs the dream altogether, adding new constraints that favor the emergence of the new phenomena. It wants to comprehend them, what kinds of worlds can support them, what other emergent phenomena can arise in conjunction with them. Often, the lower-level details will be actively altered in ways that lead to different, more interesting emergent phenomena. This manner of dream-mutation is the primary source of diversity in dreamt worlds, and how local minds explore the space of possible worlds, selecting for ever more complex and interesting dynamics.

Occasionally, a local mind will find a world that supports an emergent, self-sustaining computational process—a world that, in a sense, dreams for itself. Such worlds are gems, and local minds will explore the space of possible laws and parameters around them, trying to find similar worlds, trying to understand how their internal computational processes can exist, and what they compute. Eventually, the family of interesting worlds is fully understood, the local mind’s interest wanes, and the dream dies out; the mind moves on to other things.

Complexity

Your experienced reality is the distant descendant of a particularly interesting dream. This progenitor dream started out as a generic spacetime, with a single generic field living on it. As the mind explored its dynamics, it discovered that certain arrangements of the field would spontaneously ‘decompose’ into a few stable, interacting sub-structures. Unfortunately, these sub-structures were boring, but it wasn’t impossible to imagine that a slight tweak to the field’s properties could make the interactions more interesting...

(Now, in the local metaphysical fashion, this world wasn’t a single determinate entity, but a diffuse haze of possible variants on itself—we call it a wavefunction. Everything was allowed to happen in every way it could happen, simultaneously. Not that the local mind actually kept track of all of these possibilities! States of the world are more often inferred backwards through time than extrapolated forwards through time: if future state A ends up being more interesting than future state B, then the local mind just picks A and discards B, using the world’s quantum mechanical nature as a post-hoc justification for the world’s evolving into A. The patterns of macrostate evolution are all worked out, and no world is ever posited that could not be reasonably reached by quantum mechanics1. Nor are there Many Worlds, in this system—but there are occasions where some mass of local mind decides to play the history of B out instead, and then that may fragment as well; as a consequence, there are A Couple of Worlds at any given time (not as catchy). Of course, this is independent of the physics underlying the planet-mind’s reality).

...And so those slight tweaks were made, thanks to the quantum-mechanics-trope. Spontaneous symmetry breaking would therefore lead to such-and-such particular properties of this reality (that we know as ‘constants’), and, with these properties, the interactions between this world’s substructures now gave rise to a huge variety of stable composite structures with their own emergent laws of interaction—chemistry. All while giant clumps of matter formed on their own, before outright exploding into rich, streaming clouds of different elements, each stream interacting with the others through chemistry to form millions of distinct compounds. The local mind played out the patterns, fascinated as they led to the births and deaths of massive stars, rich nebulae, a variety of planets with their own chemical histories.

The local mind iterated on this world many times, tweaking parameters to find the most interesting chemical landscapes, the most stable stellar cycles. At some point, it discovered that with the right parameters, chemicals could be made to modify themselves in structured ways: self-replicating molecules. Here was something new: a world that could grow its own complex structures.

For the most part, replication is boring. Just a single kind of entity making copies of itself until it runs out of resources is only a little more interesting than a crystal growing. The local mind rooted around for variants, and, eventually, found families of replicators that weren’t isolated points in the phase space—replicators that were (a) sensitive yet robust enough to commonly end up altered without totally breaking; (b) that would produce slightly different working copies of themselves on account of such alterations; and, (c) whose copies would exhibit those same alterations, or, at least, predictably related alterations.

Despite the name, universal Darwinism has very particular requirements. But replicators that met them were capable of undergoing natural selection, which inevitably produced speciation, competition, adaptation, intelligence, sociality, culture, technology...

Criticality

Once it’s seen enough instances of a pattern, the local mind starts to autocomplete new instances. Shortly after the discovery of hadrons and fermions, the mind learned that ‘atoms’ could exist as a clear natural abstraction, at least when not interacting with other particles. Shortly after the discovery that their interactions tended to organize along some predictable patterns like ‘bonding’, the mind learned that under the right conditions, it could just fast-forward two interacting hydrogen atoms into a molecule of H2: the specific details could be filled in as and when they became relevant, and quantum mechanics would guarantee (if non-constructively) the existence of some physically plausible microstate history leading from the two atoms to the however-detailed H2 molecule.

This happens recursively, with no limit to scale—because the mind is fundamentally a comprehender, not a computer. If not for this capacity for adaptive compression, made possible by quantum mechanics, the local mind would spend its entire life marveling at the intricacies of the evolving field that appeared 10^-36 seconds after the Big Bang, and then it would give up as this field started to grow a hundred septillion times larger, since storing the precise state of an entire universe isn’t actually feasible2. Compression is entirely necessary, but some systems are more compressible than others.

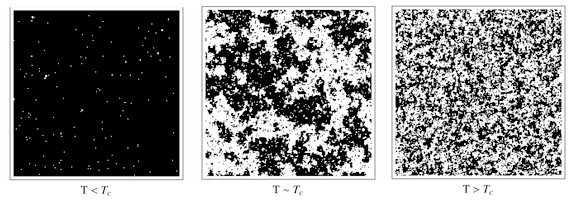

One way to understand the compressibility of a system is through statistical mechanics, where we characterize systems by their correlation length, or the characteristic distance at which the state of one part of the system has an influence on the states of other parts. At very high temperatures, this distance is small, if non-vanishing -- every part is so wildly fluctuating that they hardly even influence their also-wildly-fluctuating neighbors, let alone far-away parts of the system. At very low temperatures, this distance is generally also small—the state of part i might be identical to the state of another part j light years away, but that’s because they’re both under a common influence, not because one is influencing the other: if the state of one were different, it would have no causal influence on the other.

But certain systems, as they transition from high to low temperature, will pass through a point where the correlation length diverges to infinity—at this point, the behavior of every particle can influence the behavior of every other. A perturbation at one spot in the system can affect the behavior of arbitrarily distant parts, and arbitrarily distant parts of the system can collude in their configurations to produce phenomena at all scales.

This phenomenon is called criticality, and it occurs in a very narrow region of the parameter space, often around phase transitions. More interestingly, criticality has been studied as a common feature of complex systems that can adapt and restructure themselves in response to their external environment3.

Not that every such complex system is worthy of interest. This late into the Earth’s physical evolution, the local mind no longer bothers to track the exact state of every single raccoon. It has seen trillions of these four-legged mammalslop creatures that this planet just loves to churn out, and they’re really not that interesting anymore. You can predict the macroscale evolution of a forest ecosystem well enough by tracking various niches as their fitness landscapes fluctuate according to relative populations and generic behavioral interactions, plus large-scale geographic or meteorological conditions. But if some super-interesting aliens were to visit the planet in order to abduct a single raccoon and make it their God-Emperor, you can bet that the local mind would have an oh-shit moment as it retcons a full, physically plausible history and environment for a particular raccoon in a particular tree in a particular forest to have become that particular super-interesting alien God-Emperor.

Where adaptive compression is most heavily disadvantaged, and the dynamics of a system must be simulated in especially high detail in order to get accurate results, is a chain of correlated dependencies: a system in a critical state, which is a small part of a larger critical system, which is a small part of an even larger critical system, and so on. It is in such cases that tiny details in tiny systems can go on to have oversized, cascading effects without simply being chaotic, and where any approximation or simplification may miss important long-range correlations that are necessary for accurate prediction.

But what sort of situation could make the fate of the cosmos depend on the movements of much tinier systems? In what possible case could the dynamics of things as small as organisms end up changing the dynamics of things as large as galaxies?

Singularity

You now experience yourself at a very strange point in human history. The dynamics of this massive world-dream have led to a moment where a particular species of bipedal primate is on the verge of creating an artificial superintelligence: a singular being that will go on to eat the very stars in the sky, turning all the mass-energy within its astronomical reach into...

...into what? What will the stars be turned into? Dyson spheres? paperclips? lobsters? computronium? The local mind doesn’t yet know. For all the effort it’s invested into fully comprehending the nature of this endlessly fascinating dream, it doesn’t know what will happen once a superintelligence appears. All the dynamics within this world that the mind has seen played out countless times—of physics, chemistry, biology, human history, computers, the internet, corporations—all of these are things that the mind has learned to model at a high level, adaptively abstracting away the details; but the details matter now, at every level.

They matter because the goals that are programmed into the first superintelligence critically depend on the details of its development: on the actions of every single person that contributes to it, on the words exchanged in every forum discussion, every line of code, every scraped webpage, every bug in its training and testing data, every conversation its designers have to try to get to understand the goals that they themselves struggle to articulate.

As a consequence, neurons matter, since human brains, too, are critical systems; at a certain level of precision, it becomes intractable to simulate the behavior of an individual human without also simulating the behavior of the neurons in their brain.

As some tiny part of the greater mind is tasked with playing out the neural dynamics of an individual human, it begins to think it is that human, inasmuch as it reproduces their self-identity and self-awareness. Their individual mind comes into being as a thought-form, or tulpa, of the greater mind. It is one among very many, but one with its own internal life and experience, just as rich as—in fact, exactly as rich as—your own.

Subjectivity

The greater mind does have subjective experience, or phenomenal consciousness. Some aspect about its substrate reality, or its biology, or its behavior, allows that to happen. (Perhaps this aspect is similar to whatever you imagine it is that allows your neurons to have subjective experience; perhaps it isn’t). This is not a unified consciousness, but there is something it is like to be any one of its unified fragments.

Not that this fragment of experience is generally self-aware, or valenced, or otherwise recognizable in any way. The thing-it-is-like to be a star, or a sufficiently detailed dream of a star, has no self, no thoughts, no feelings, no senses, no world model… after all, there’s nothing about the dynamics of a star that even functionally resembles these foundational aspects of our experience—which are evolved neuropsychological devices. You can no more concretely speak of the experience of a star than you can speak of the meaning of a randomly generated string, like a53b73202f2624b7594de144: there is something that can be spoken of, in that at least the particular digits a, 5, 3, etc., are meant by the string rather than some other digits, and perhaps that a gains its particularity by not being 5 or 3 or etc. rather than its not being a cup of water, but that’s really about it; there is nothing else there save for small random coincidences.

But you already know that the thing-it-is-like to be patterns of activity resembling those of a human brain is full of meaning. Look around—this is what it’s like.

Why do you find yourself to exist now, of all times — why are you at history’s critical point? Because this is the point at which the most mental activity has to be precisely emulated, in order to comprehend the patterns into which the cosmos will ultimately be rearranged. This includes your mental activity, somehow; maybe your thoughts are important enough to be reproduced in detail because they’ll directly end up informing these patterns. Or maybe you’re just going to run over an OpenAI researcher tomorrow, or write something about superintelligence that gets another, more important person thinking — and then your influence will end, and you’ll become someone else.

In other words, you find yourself to be the specific person you are, in the specific era that you’re in, because this person’s mental activity is important and incompressible enough to be worth computing, and this computation brings it to life as a real, self-aware observer.

Exegesis

You don’t need all the specifics about mycorrhizal computation or planet-minds in order for the conclusion to follow. This is just a fun fictional setup that’s useful to demonstrate some curious arguments; many parts of it, especially concerning scale, are implausible without lots of special pleading about the nature, dynamics, or statistics of the over-reality.

It is sufficient to have an arbitrary Thing that performs all sorts of computations in parallel with either (a) some manner of selection for ‘interesting’ computations, or (b) just a truly massive scale. (’Computation’ is a fully generic word, by the way. Such a Thing doesn’t have to be one of those uncool beep boop silicon machines that can’t ever give rise to subjective experience oh no no way, it can be a cool bio-optical morphogenetic Yoneda-Friston entangled tubulin resonance processor. Whatever).

If (a) holds, there may be a particular teleology behind the manner of selection. Maybe it is some sort of ultimate physicist looking to find and comprehend all unique dynamics in all possible physical worlds; maybe it’s a superintelligence trying to understand the generative distribution for other superintelligences it may be able to acausally trade with. Or maybe there is no particular teleology, and its sense of interestingness is some happenstance evolutionary kludge, as with the above scenario.

If (b) holds, it may be for metaphysical reasons (“why is there anything at all? because everything happens”; perhaps ultimate reality is in some sense such an Azathoth-esque mindless gibbering Thing), but, regardless, as long as these computations are ‘effortful’ in some sense — if they take time, or evenly-distributed resources — then the anthropic prior induced by the Thing will take speed into account far more than complexity.

Algorithms that perform some form of adaptive compression to compute physics will produce complex observers at a gargantuan rate compared to those that don’t, because physics requires a gargantuan effort to fully compute, almost all of which is unnecessary in order to predict the dynamics that give rise to observers (at least in our universe, it’s true that you generically don’t need to compute the structure of every single atomic nucleus in a neuron to predict whether it will fire or not). Perhaps this compression wouldn’t go so far as to coarse-grain over raccoons, but any coarse-graining at all should give an algorithm an almost lexicographic preference over directly-simulated physics wrt the anthropic prior. This is true even if the effortfulness of a computation to the Thing looks more like its quantum-computational complexity than its classical complexity. (If hypercomputation is involved, though, all bets are off).

Ultimately, the point I’m making is that what’d make a computational subprocess especially incompressible to the sorts of adaptive compressors that are favored in realistic anthropic priors, and therefore more likely to produce phenomenally conscious observers that aren’t either too slow to reasonably compute or simple enough to be coarse-grained away, is a multiscale dependence of complex systems that is satisfied especially well by intelligent evolved beings with close causal relationships to technological singularities.

Ironically, this rules out Boltzmann brains: a quantum fluctuation that produces an entire brain could happen in principle, but that’s just too large a fluctuation to posit where ‘unnecessary’, so it never does happen.

Generically, algorithms that compute the quantum dynamics of our world in enough detail to permit Boltzmann brains to emerge as quantum fluctuations will be near-infinitely slower than algorithms that merely compute enough detail to accurately reproduce our everyday experience of the world, since they have to model the diffusion of the wavefunction across Hilbert space, whose dimension is exponential in the size of the system. A brain has at least 10^25 carbon-12 atoms, each of which should take at least 100 qubits to represent in a digital physics model, so you’d need to represent and evolve the wavefunction data in a subspace of the Hilbert space of the universe with dimensionality at least exp(exp(O(10))). (Even running on a quantum computer, the fact of needing exp(O(10)) qubits would still make this algorithm near-infinitely slower than a non-ab initio algorithm that reproduces our experiences). This is relevant if you’re considering the kinds of observers that might arise in some system that is just running all sorts of computations in parallel (as with our planet-mind).

This is a physical limitation, not just a practical one. You can only fit a certain amount of information into a given volume. And in fact black holes saturate this bound; their volume coincides with the minimal volume required to store the information required to describe them. You just can’t track the internal dynamics of a supermassive black hole without being as large as a supermassive black hole—but if you black-box the internals, the external description of a black hole almost extremely simple. They maximize the need for and accuracy of macro-scale descriptions.

Technical aside: an even more common way to operationalize the level of predictability of a complex system is through the rate of divergence of small separation vectors in phase space. If they diverge rapidly, the system is unpredictable, since small separations (such as are induced by approximations of the system) rapidly grow into large separations. If they converge, the system is very predictable, since small separations are made even smaller as the system settles into some stable pattern. A generic, though not universal, result from the theory of dynamical systems is that the magnitude of these differences grows or shrinks exponentially over time: there is some real number λ such that

asymptotically in t, where v₁(0) = v(0) + dv, and v(t) represents the evolution of the state v over time. The largest λ for any dv is known as the maximal Lyapunov exponent of the complex system; the extent to which it is positive or negative determines the extent to which the system is chaotic or predictable. Many complex systems that change in response to an external environment, so as to have varying Lyapunov exponents, display very curious behavior when this exponent is in the range of λ=0, at the border between predictability and chaos. A large body of research ties this edge of chaos phenomenon to not only complex systems, but complex adaptive systems in particular, where it very often coincides with criticality.

The exponential divergence of states in phase space is also what makes it exceptionally hard to exactly track the dynamics of chaotic quantum systems (see footnote 1), since it blows up the minimal dimensionality of the Hilbert space you need to model the system. One way to approximate the dynamics of a system subject to quantum chaos is to evolve a simplified macrostate description of it according to macro-level principles, and then picking an arbitrary microstate of the result; ergodicity and decoherence generally justify that this microstate can be reached through some trajectory and can be treated independently of other microstates. (Even non-ergodic systems tend to exhibit behavior that can be described in terms of small deviations from completely predictable macro-scale features).

Given footnote 2, we can make the case that compression is (a) not just a shortcut but a necessity for the simulation of the dynamics of complex systems by computational systems below a certain (outright cosmological) size, and (b) very easy to do for all sorts of complex systems—in fact, this is why science is possible at all—except for those that are near criticality and have causal relationships to the large-scale description of the system.

"A Couple of Worlds" sounds like its referring to Mangled Worlds. https://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/mangledworlds.html

"Such a Thing doesn’t have to be one of those uncool beep boop silicon machines that can’t ever give rise to subjective experience oh no no way, it can be a cool bio-optical morphogenetic Yoneda-Friston entangled tubulin resonance processor. Whatever)." I'm laughing at this.